Difference between revisions of "Setup and tuning of recurves and longbows"

(New page: {| width="620" align="left" |- bgcolor="#999966" align="left" valign="top" | colspan="2" height="10" | <font size="4" face="Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif">'''Setup and tuning of recurves an...) |

m |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by one user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

| colspan="2" height="10" | <font size="4" face="Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif">'''Setup and tuning of recurves and longbows'''</font> | | colspan="2" height="10" | <font size="4" face="Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif">'''Setup and tuning of recurves and longbows'''</font> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="9" width=" | + | | rowspan="9" width="608" align="left" valign="top" | |

| − | <span class="archer1">'''''By Cleve Cheney'''''</span><span class="archer1">The visual differences between a com-pound, recurve and longbow are obvious. As one delves deeper into the mysterious world of archery physics, the differences become even more pronounced. Com-pound bows operate to a very different set of parameters than those of recurve or longbows. </span><span class="archer1">Let us look at some of the fundamental differences: </span><span class="archer1"><br />'''Release method'''<br /> Compound bows are shot with either fingers or release aid. When using fingers, the shot more closely approximates that of a recurve or longbow. </span><span class="archer1">Recurves and longbows are shot using fingers as the method of bowstring release. Shooting with a release aid induces less paradox (lateral bending) of the arrow shaft and when correctly tuned, leaves the bow pretty straight out. With fingers, bending of the shaft is radically increased. The essential element in choosing the correct shaft for a recurve or longbow is the TIMING of these bends. When the finger shooter releases the string the shaft will undergo three bends:</span><span class="archer1">'''For a right handed shooter:'''<br /> Bend 1: As the string is released, the nock moves suddenly to the left and the leading end of the arrow pushes into and rebounds from the arrow plate or plunger. The first bend of the shaft is in towards the bow.</span><span class="archer1">Bend 2: If the arrow is correctly spined, the arrow bends outwards, away from the bow when it is about halfway out of the bow. This provides clearance for the central portion of the shaft as it passes the riser window.</span><span class="archer1">Bend 3: The shaft bellies inward as the fletching passes the riser, providing the necessary clearance for the nock end as it moves past to the left of the arrow rest.<br /> An incorrectly spined shaft will bend at the wrong times, resulting in extremely erratic, unpredictable and inaccurate flight. We will look later at how to test for correctly spined arrows for a recurve or longbow.</span><span class="archer1">'''Arrow rest'''<br /> On a longbow with little centreshot cutout, you need a rest that will keep the arrow close to the window. No cushion plunger will be used. Some archers prefer to shoot "off the shelf" - resting directly on the bow shelf. In primitive bows (self wood bows) and in some longbows there is no centreshot cutout and the index finger of the bow hand is used as the arrow rest.</span><span class="archer1">The window cutout of wood-handled recurve bows is not cut past centre and stick-on arrow rests are used with cushion plungers. These support the arrow from the side as opposed to a shoot-through rest which supports the arrow from below. Metal riser recurves generally have enough cut beyond centre so that almost any rest setup can be used. When shooting with fingers, side-supporting rests must be used.</span><span class="archer1">'''Draw force curves'''<br /> When the string is released in a recurve or longbow the maximum force is applied immediately to the arrow. When a compound bowstring is released, the force is applied gradually and peaks later on during the shot. Generally speaking, for the same poundage bow, a stiffer spined arrow must be used in a recurve or longbow as opposed to a compound.</span><span class="archer1">'''Sights and shooting style'''<br /> Compound bows are usually shot using sights. Recurve bows can be shot with or without sights. Longbows/self bows are generally shot without sights using instinctive shooting techniques. An archer shooting a compound bow enjoys the advantage of "letoff" reduced holding weight at full draw and can hold the bow steady for a few seconds to take careful aim before releasing the arrow. When shooting a recurve bow there is no letoff and the archer holds maximum draw weight at his draw length. The arrow is released much sooner. In heavy poundage recurve and longbows the arrow is released almost as soon as the anchor point is reached.</span><span class="archer1">'''<br /> BASIC BOW SETUP FOR A RECURVE AND LONGBOW - USING FINGER RELEASE''' (see Figure 1)</span><span class="archer1">'''Tiller'''<br /> In a bow with replaceable limbs tiller is measured from the bowstring to the point where the riser and limbs meet. In one-piece bows the tiller is measured from the bowstring to the belly at the "fadeout," the point where the wedge in the riser tapers to a point. In traditional one-piece recurves and longbows, bows are tillered to produce a stiffer lower limb i.e. the bowstring to fadeout measurement on the upper limb is greater than on the lower limb. On a one-piece bow this cannot be altered other than by removing limb material. On modern take-down recurves and longbows tiller can be adjusted by screwing limb bolts in or out. Limb bolts are screwed in opposite directions (top and bottom limb) to change tiller. In adjustable bows tiller should be set equal or 2-3mm longer on the upper limb. </span><span class="archer1">'''Brace height'''<br /> Brace height is the distance from the bowstring to the point on the bow handle where your bow hand exerts pressure on the handle. In old English this was referred to as "fistmele" a distance of approximately 8" measured by making a fist and extending the thumb out sideways at 90o to the fingers. If the brace height is less than 8" a painful slap of the bowstring against the wrist will result. Apart from the obvious discomfort this will also cause erratic and inaccurate arrow flight. To adjust brace height remove one end of the bowstring from the nocking groove and twist it to shorten the string (which will increase brace height) and unwind it to lengthen it (which will decrease brace height).</span><span class="archer1">'''Nocking point'''<br /> Place a bow square on the arrow rest and clip it onto the bowstring. Measure a distance of 11-12mm up from the 90o horizontal the bow square makes with the bowstring and, using nocking pliers, crimp a nock set on the string. Crimp a second nock set on the string above this one to prevent it moving. This nocking point will give good arrow flight and can be adjusted slightly up or down to cancel out porpoising (vertical arrow oscillation). Conduct a paper test (see previous issue) to tune out porpoising. Now move on to shaft alignment.</span><span class="archer1">'''Shaft alignment''' (see Figure 2)<br /> True centre shot adjustment is not possible on most recurve and longbows because of the design features of the bows. Apart from this one has to bear the fact in mind that arrow paradox must be taken into account (the "bending" of the arrow we spoke about earlier). For this reason the arrow tip must be 3-6mm outside the line of the bowstring when viewed from behind. This will facilitate bending of the arrow at the correct times. Conduct the paper test to achieve the shaft alignment that gives the best arrow flight - as close as possible to a "bullet" hole.</span><span class="archer1">'''Fletch clearance''' (see Figure 3)<br /> The position of the fletches in relation to the arrow rest and the riser will determine the amount of fletch contact there will be with the bow. It should be a minimum - preferably no contact at all - desirable but not always possible. Play around with the fletching, rest, riser variables until minimum fletching contact is achieved. Figure 3 shows correct fletch alignment for a fold-away "Flipper" rest. You can spray talc powder onto the fletching and arrow rest/riser to test for fletch contact which will show up as streaks through the fine powder.</span><span class="archer1">'''Cushion plunger'''<br /> A cushion plunger is a spring-loaded button which applies pressure to the side of the arrow shaft at the arrow rest. The dynamic spine (stiffness) of the arrow can be varied by increasing or decreasing the spring tension. See bare shaft planing test.</span><span class="archer1"><br />'''ARROW SELECTION'''<br /> The proper choice of arrow spine is far more critical for finger shot bows than for release aids. Use arrow spine charts. Look under the recurve/longbow column. Go down to where you see the peak draw weight of your bow then go to the right, along this column, to where you see the length of the arrow you shoot. There will be a number of arrow spines specified. These are good starting choices with which you can now experiment to see which one works best in your particular bow.</span><span class="archer1">Bare shaft planing test to check for correct arrow spine (see Figure 4). At a distance of 15m shoot 3 fletched and 3 unfletched arrows into a target butt. If the bare shafts impact to the left of the fletched arrows it is an indication that the spine is too stiff. To correct, shoot a weaker spined arrow or decrease spring tension on the cushion plunger. If they impact to the right of the fletched shafts they are too limber (spine is too weak). To correct, shoot a stiffer arrow or increase spring tension on the cushion plunger.</span><span class="archer1">The basic setup of the recurve or longbow is complete. Go out and give it a test and make adjustments using the paper test and bare shaft planing test. Remember when tuning to work on only one variable at a time.</span><span class="archer1">'''Good shooting and God bless'''</span>'''<span class="body100">.</span>''' | + | <span class="archer1">'''''By Cleve Cheney'''''</span> |

| + | |||

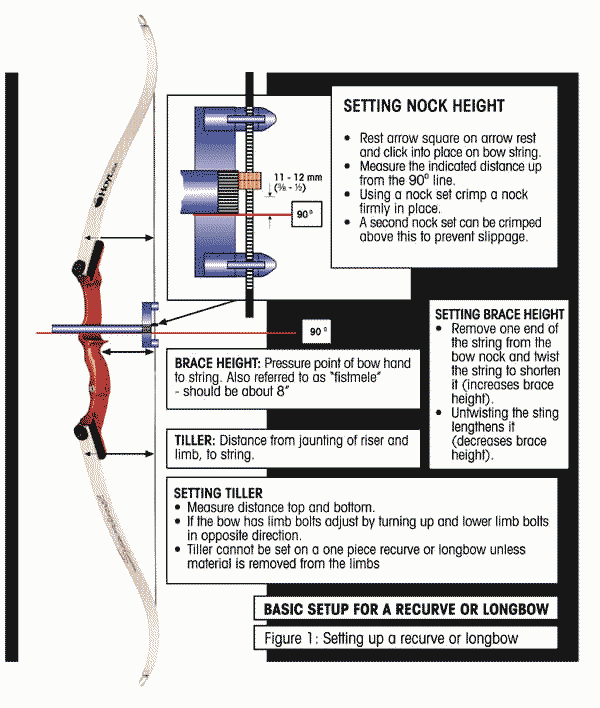

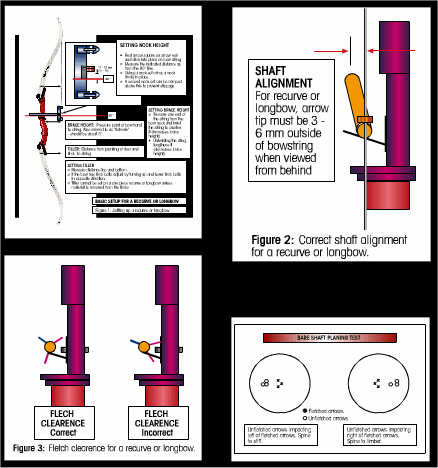

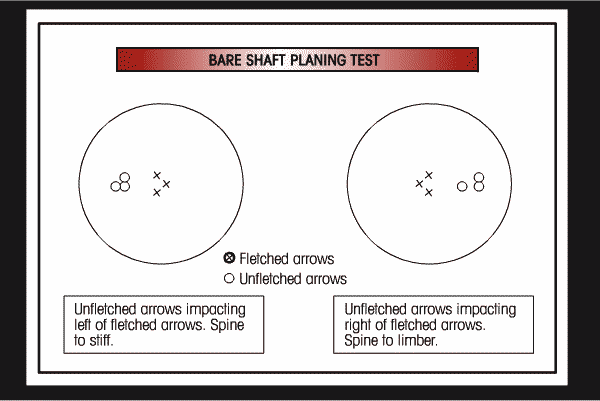

| + | <span class="archer1">The visual differences between a com-pound, recurve and longbow are obvious. As one delves deeper into the mysterious world of archery physics, the differences become even more pronounced. Com-pound bows operate to a very different set of parameters than those of recurve or longbows. </span><span class="archer1">Let us look at some of the fundamental differences: </span><span class="archer1"><br />'''Release method'''<br /> Compound bows are shot with either fingers or release aid. When using fingers, the shot more closely approximates that of a recurve or longbow. </span><span class="archer1">Recurves and longbows are shot using fingers as the method of bowstring release. Shooting with a release aid induces less paradox (lateral bending) of the arrow shaft and when correctly tuned, leaves the bow pretty straight out. With fingers, bending of the shaft is radically increased. The essential element in choosing the correct shaft for a recurve or longbow is the TIMING of these bends. When the finger shooter releases the string the shaft will undergo three bends:</span><span class="archer1">'''For a right handed shooter:'''<br /> Bend 1: As the string is released, the nock moves suddenly to the left and the leading end of the arrow pushes into and rebounds from the arrow plate or plunger. The first bend of the shaft is in towards the bow.</span><span class="archer1">Bend 2: If the arrow is correctly spined, the arrow bends outwards, away from the bow when it is about halfway out of the bow. This provides clearance for the central portion of the shaft as it passes the riser window.</span><span class="archer1">Bend 3: The shaft bellies inward as the fletching passes the riser, providing the necessary clearance for the nock end as it moves past to the left of the arrow rest.<br /> An incorrectly spined shaft will bend at the wrong times, resulting in extremely erratic, unpredictable and inaccurate flight. We will look later at how to test for correctly spined arrows for a recurve or longbow.</span><span class="archer1">'''Arrow rest'''<br /> On a longbow with little centreshot cutout, you need a rest that will keep the arrow close to the window. No cushion plunger will be used. Some archers prefer to shoot "off the shelf" - resting directly on the bow shelf. In primitive bows (self wood bows) and in some longbows there is no centreshot cutout and the index finger of the bow hand is used as the arrow rest.</span><span class="archer1">The window cutout of wood-handled recurve bows is not cut past centre and stick-on arrow rests are used with cushion plungers. These support the arrow from the side as opposed to a shoot-through rest which supports the arrow from below. Metal riser recurves generally have enough cut beyond centre so that almost any rest setup can be used. When shooting with fingers, side-supporting rests must be used.</span><span class="archer1">'''Draw force curves'''<br /> When the string is released in a recurve or longbow the maximum force is applied immediately to the arrow. When a compound bowstring is released, the force is applied gradually and peaks later on during the shot. Generally speaking, for the same poundage bow, a stiffer spined arrow must be used in a recurve or longbow as opposed to a compound.</span><span class="archer1">'''Sights and shooting style'''<br /> Compound bows are usually shot using sights. Recurve bows can be shot with or without sights. Longbows/self bows are generally shot without sights using instinctive shooting techniques. An archer shooting a compound bow enjoys the advantage of "letoff" reduced holding weight at full draw and can hold the bow steady for a few seconds to take careful aim before releasing the arrow. When shooting a recurve bow there is no letoff and the archer holds maximum draw weight at his draw length. The arrow is released much sooner. In heavy poundage recurve and longbows the arrow is released almost as soon as the anchor point is reached.</span><span class="archer1">'''<br /> BASIC BOW SETUP FOR A RECURVE AND LONGBOW - USING FINGER RELEASE''' (see Figure 1)</span><span class="archer1">'''Tiller'''<br /> In a bow with replaceable limbs tiller is measured from the bowstring to the point where the riser and limbs meet. In one-piece bows the tiller is measured from the bowstring to the belly at the "fadeout," the point where the wedge in the riser tapers to a point. In traditional one-piece recurves and longbows, bows are tillered to produce a stiffer lower limb i.e. the bowstring to fadeout measurement on the upper limb is greater than on the lower limb. On a one-piece bow this cannot be altered other than by removing limb material. On modern take-down recurves and longbows tiller can be adjusted by screwing limb bolts in or out. Limb bolts are screwed in opposite directions (top and bottom limb) to change tiller. In adjustable bows tiller should be set equal or 2-3mm longer on the upper limb. </span><span class="archer1">'''Brace height'''<br /> Brace height is the distance from the bowstring to the point on the bow handle where your bow hand exerts pressure on the handle. In old English this was referred to as "fistmele" a distance of approximately 8" measured by making a fist and extending the thumb out sideways at 90o to the fingers. If the brace height is less than 8" a painful slap of the bowstring against the wrist will result. Apart from the obvious discomfort this will also cause erratic and inaccurate arrow flight. To adjust brace height remove one end of the bowstring from the nocking groove and twist it to shorten the string (which will increase brace height) and unwind it to lengthen it (which will decrease brace height).</span><span class="archer1">'''Nocking point'''<br /> Place a bow square on the arrow rest and clip it onto the bowstring. Measure a distance of 11-12mm up from the 90o horizontal the bow square makes with the bowstring and, using nocking pliers, crimp a nock set on the string. Crimp a second nock set on the string above this one to prevent it moving. This nocking point will give good arrow flight and can be adjusted slightly up or down to cancel out porpoising (vertical arrow oscillation). Conduct a paper test (see previous issue) to tune out porpoising. Now move on to shaft alignment.</span><span class="archer1">'''Shaft alignment''' (see Figure 2)<br /> True centre shot adjustment is not possible on most recurve and longbows because of the design features of the bows. Apart from this one has to bear the fact in mind that arrow paradox must be taken into account (the "bending" of the arrow we spoke about earlier). For this reason the arrow tip must be 3-6mm outside the line of the bowstring when viewed from behind. This will facilitate bending of the arrow at the correct times. Conduct the paper test to achieve the shaft alignment that gives the best arrow flight - as close as possible to a "bullet" hole.</span><span class="archer1">'''Fletch clearance''' (see Figure 3)<br /> The position of the fletches in relation to the arrow rest and the riser will determine the amount of fletch contact there will be with the bow. It should be a minimum - preferably no contact at all - desirable but not always possible. Play around with the fletching, rest, riser variables until minimum fletching contact is achieved. Figure 3 shows correct fletch alignment for a fold-away "Flipper" rest. You can spray talc powder onto the fletching and arrow rest/riser to test for fletch contact which will show up as streaks through the fine powder.</span><span class="archer1">'''Cushion plunger'''<br /> A cushion plunger is a spring-loaded button which applies pressure to the side of the arrow shaft at the arrow rest. The dynamic spine (stiffness) of the arrow can be varied by increasing or decreasing the spring tension. See bare shaft planing test.</span><span class="archer1"><br />'''ARROW SELECTION'''<br /> The proper choice of arrow spine is far more critical for finger shot bows than for release aids. Use arrow spine charts. Look under the recurve/longbow column. Go down to where you see the peak draw weight of your bow then go to the right, along this column, to where you see the length of the arrow you shoot. There will be a number of arrow spines specified. These are good starting choices with which you can now experiment to see which one works best in your particular bow.</span><span class="archer1">Bare shaft planing test to check for correct arrow spine (see Figure 4). At a distance of 15m shoot 3 fletched and 3 unfletched arrows into a target butt. If the bare shafts impact to the left of the fletched arrows it is an indication that the spine is too stiff. To correct, shoot a weaker spined arrow or decrease spring tension on the cushion plunger. If they impact to the right of the fletched shafts they are too limber (spine is too weak). To correct, shoot a stiffer arrow or increase spring tension on the cushion plunger.</span><span class="archer1">The basic setup of the recurve or longbow is complete. Go out and give it a test and make adjustments using the paper test and bare shaft planing test. Remember when tuning to work on only one variable at a time.</span><span class="archer1">'''Good shooting and God bless'''</span>'''<span class="body100">.</span>''' | ||

| width="200" height="233" align="left" valign="top" | | | width="200" height="233" align="left" valign="top" | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

| + | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Setup and tuning of recurves and longbows 01.png]] | ||

| + | *Setting up a recurve or longbow | ||

| + | |||

| + | | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Setup and tuning of recurves and longbows 02.png]] | ||

| + | *Correct shaft alignment for a recurve or longbow. | ||

| + | *Fletch clearance for a recurve or longbow. | ||

| + | |||

| + | | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Setup and tuning of recurves and longbows 04.png]] | ||

| + | *Bare shaft planing test to check for correct arrow spine . Use the same aiming point for both fletched and bare shafts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | | ||

| + | |||

| + | | ||

[[Category:Sports and Recreation]] | [[Category:Sports and Recreation]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Archery]] | ||

Latest revision as of 07:26, 30 June 2007

| Setup and tuning of recurves and longbows | |

|

By Cleve Cheney The visual differences between a com-pound, recurve and longbow are obvious. As one delves deeper into the mysterious world of archery physics, the differences become even more pronounced. Com-pound bows operate to a very different set of parameters than those of recurve or longbows. Let us look at some of the fundamental differences: |

|

- Setting up a recurve or longbow

- Correct shaft alignment for a recurve or longbow.

- Fletch clearance for a recurve or longbow.

- Bare shaft planing test to check for correct arrow spine . Use the same aiming point for both fletched and bare shafts.